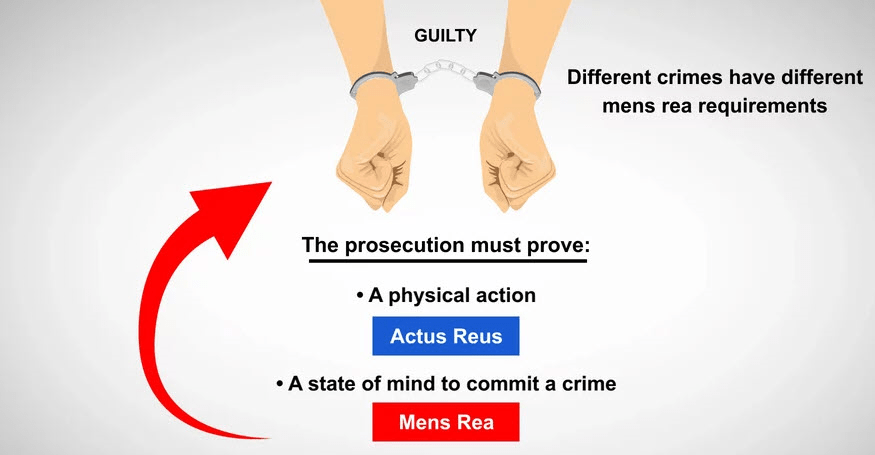

Today, I wanted to debate about a philosophical question. The question is: Can thoughts and a person's intention be punished? Let's say someone plans a murder but is caught before committing it. According to legal law, the person isn't considered guilty because, despite planning, they didn't act. Before I jump right into the article, let me explain some related notions: mens rea refers to the offender's mental state at the time of the crime, whereas actus reus relates to the physical act of committing a crime.

Let's try a real-life example. For example, you're in class and you plan to copy the homework you haven't done last night using a notebook you borrowed from your friend. But you're in the front row, and the teacher keeps an eye on you throughout the lesson. Therefore, you can't pass the homework. In such a situation, neither the teacher can discipline you, nor can you carry out your plan. Ultimately, this action will remain merely a plan you planned with your friend but didn't follow through, and it won't harm anyone. Even if the teacher catches you just as you're about to take the notebook, their trust might be broken, but they still can't prove you intended to copy.

I believe this is a requirement of free will, and no one can be deprived of this right. Just because someone intends to do something doesn't necessarily mean they will do it. In psychology, there's no direct correspondence between intention (the desire/decision to do something) and behavior (the actual action taken). People often intend to do something but don't do it, or they do something they never intended to do. There are several theories that attempt to explain this gap:

Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991): Behavior is determined by three factors: intention, self-efficacy, and environmental/social conditions. In other words, even if there is intention, if there is no opportunity or social pressure, the behavior may not occur.

Impulse vs. control models:People’s impulsive nature sometimes overshadows their intentions, such as indulging in sweets at night while intending to diet.

Psychodynamic approaches: Unconscious processes can sabotage a person's intentions; that is, the person may actually act contrary to their own intentions.

Legally, this means that a person's bad intention is no guarantee that the behavior will occur. Because psychological processes intervene, there is ambiguity between intent and action.

To consider the issue from another perspective, Orwell's "thoughtcrime" in 1984 demonstrates the danger of totalitarian regimes: in such regimes, simply thinking is a crime. Authoritarian regimes legitimize the suppression of intentions; security trumps freedom. Living in such a dystopia would not be an enjoyable experience for anyone except dictators. Furthermore, the state's abuse of this limit, labeling opposition as a "potential threat," directly impacts the willpower of the people.

A Kantian perspective, on the other hand, prioritizes the moral value of intention: Bad intentions can be considered morally wrong.

In my opinion, from a philosophical perspective, bad intention carries moral weight, but legal sanctions generally require the "act." Politics and psychology complicates this debate further: the balance between the state's concern for security and the individual's right to free thought is one of the most difficult questions modern societies must resolve. However, I believe that if an individual or a group is suspected of committing a bad act even a crime, they cannot be punished, but precautions can be taken against what they might do.

Leave a comment